Welcome to Citizen Scholar! Since launching four weeks ago, we’re already reaching hundreds of subscribers - thank you for your continued support. If you enjoy our writing and believe in our mission - to bring together a community of readers who value the study and discussion of important ideas - we humbly ask you to share Citizen Scholar with your family members and friends that may enjoy it. We’re grateful for your support and we look forward to continuing on this journey with you! The contents of the audio and text formats are identical and meant to accommodate your preferences.

Introduction

Last week’s post ended on a challenging note. Our biggest takeaway from The Exponential Age was that societal institutions may be ill-equipped to handle the transformative impact of exponential technological progress. The book’s author proposed a few potential solutions but stopped short of providing a comprehensive framework for tackling the full array of issues. We don’t propose to have the breakthrough just yet. However, we were inspired to dust off a classic that could serve as a starting point.

Why Nations Fail was initially released in 2012. Barack Obama was serving his first term as President of the United States, and the Arab Spring was still unfolding. At the time, author James Robinson was a political scientist at Harvard, and his co-author Daron Acemoglu was an economist at MIT. In Why Nations Fail, they sought to explain wealth inequality between countries around the world. The result was a serious academic work of comparative economic development, but its supreme readability and the force of its arguments thrust it into public debates and quickly made it a bestseller. The book is still on the syllabus of many political science courses in universities today.

Popular frameworks for evaluating why some countries are poorer than others include focusing on geographic factors, cultural differences or relative skill of leadership. Acemoglu and Robinson instead proposed a framework that focused on the qualities of and incentives inherent in nations’ institutions. This focus on the nature and relative merit of various institutions is what made Why Nations Fail such an appealing follow-up to The Exponential Age.

Toward a Theory of Institutions

According to Why Nations Fail:

“Each society functions with a set of economic and political rules created and enforced by the state and the citizens collectively. Economic institutions shape economic incentives: the incentives to become educated, to save and invest, to innovate and adopt new technologies, and so on. It is the political process that determines what economic institutions people live under, and it is the political institutions that determine how this process works.”

According to Why Nations Fail, long term economic growth and widespread prosperity can only be achieved in a nation with inclusive economic institutions. The authors also argue that inclusive political institutions are a prerequisite to lasting inclusive economic institutions; in the absence of inclusive political institutions, factions in the political system will organize economic systems to benefit themselves at the cost of society. These would represent extractive economic institutions maintained by extractive political institutions. Below are examples of the characteristics embodied by each type of institution, as provided by the authors:

Inclusive economic institutions:

Inclusive property rights

Law and order

Markets and state support (public services and regulation) for markets

Open to relatively free entry of new businesses

Uphold contracts

Access to education and opportunity for the great majority of citizens

Inclusive political institutions:

Political institutions allowing broad participation (pluralism)

Constraints and checks on politicians

Rule of law (closely related to pluralism)

But also some degree of political centralization / state capacity to be able to effectively enforce law and order

Extractive economic institutions:

Lack of law and order

Insecure property rights

Entry barriers and regulations preventing functioning of markets and creating a non-level playing field

Extractive political institutions:

Political institutions concentrating power in the hands of a few, without constraints, checks and balances or “rule of law”

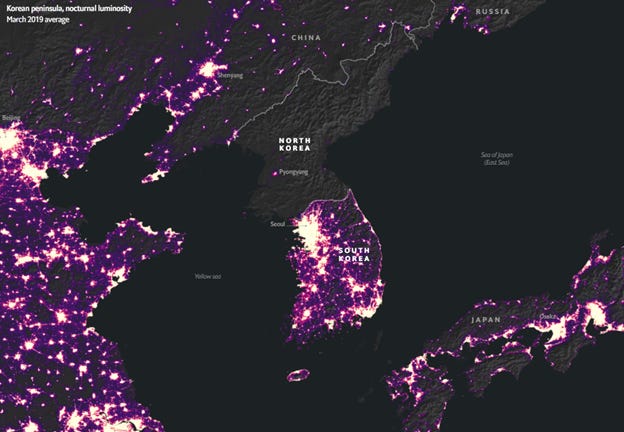

The argument made in Why Nations Fail is supported by plenty of examples the authors detail throughout the book, which themselves range from ancient Rome to the modern Korean peninsula. The divergent fates of Korean families stuck on opposite sides of the 38th parallel once fighting ended in the Korean War is an accessible case study.

Other case studies illustrate more nuanced elements in the authors’ theory. One particularly interesting, if potentially controversial, example seeks to explain why inclusive economic institutions emerged earlier in England than in other European nations. The authors emphasize how small differences at “critical junctures” in history can compound and lead to large differences centuries later. Feudal hierarchies dominated almost all of Europe when the Bubonic Plague (Black Death) first struck in the 14th century. The death and disorder was severe, and when it passed, feudal lords had trouble finding serfs to work on their lands. Many had died, while many traumatized survivors were focused on enjoying their precious lives instead of laboring in fields. In 1351, the English monarchy responded by mandating that peasants become serfs to any lord who would pay them at prevailing pre-plague wages.

This attempt at making economic institutions more extractive failed however, as enforcement was difficult and came to an end after a traumatic peasant revolt in 1381. Feudal labor requirements were gradually eliminated, an inclusive labor market emerged and wages rose. On the other hand, eastern European feudal lords responded to the same labor scarcity issues by expanding their land holdings and making labor arrangements even more extractive via higher taxes and forced labor requirements. The authors attribute their ability to do this to a small difference: these feudal lords were slightly better organized than their English counterparts, and towns in eastern Europe were generally weaker and less populous. This institutional difference continued to compound as eastern grain became a cash crop for sale to western Europe around the year 1500, increasing the incentive to extract economic value from peasants producing cash crops. This compounding effect is further elaborated in examples from around the world that demonstrate how institutions can develop in what the authors call “virtuous circles” or “vicious circles”.

Theory Applied to Reality

As one might expect, not everyone loves this framework. Bill Gates took issue with the authors’ arguments about the limited efficacy of foreign aid and wrote a critical review, which the authors dismissed rather strongly. We don’t think the framework in Why Nations Fail is a master theory for all social sciences that can explain every edge case in global economic inequality, but we do think it’s a useful and well-supported model for approaching comparative economic development.

Applying this model to the problems identified in The Exponential Age yields a few important insights. Those who accept the conclusions of Why Nations Fail will worry about inclusive economic institutions being maintained amidst exponential technological progress. Protecting property rights, state support for markets, free entry for new competitors, the sanctity of contracts and access to education and opportunity for the majority of citizens are useful guiding lights for policymakers. The political tools that can help generate these economic institutional outcomes should focus on pluralism in political participation, avoiding censorship where possible, preventing powerful technologies from becoming frightful tools in the hands of an extractive elite, and properly regulating technologies so that their operators continue to create more value for society than they extract.

Theory Applied to China

We also can’t help but apply the Why Nations Fail model to recent events in China. Acemoglu and Robinson insist that economic growth will not be sustainable in the long run if political institutions are extractive. China has benefitted in recent decades from allowing the formation of more inclusive economic institutions such as freer labor markets and greater property rights. However, as the book predicted, there are signs that extractive political institutions of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) are taking steps to reverse this progress in Chinese economic institutions. It’s difficult to get accurate information about this process given the lack of free press in China, but the process appears to be following the mechanism suggested in Why Nations Fail: political elites overseeing extractive economic institutions will eventually seek to roll back inclusive economic institutions when the wealth produced creates alternative factions of elites and when the effects of creative destruction in society can potentially destabilize the political order.

It has long been dangerous to be a Chinese billionaire, with these entrepreneurs typically having a higher probability of being imprisoned for corruption than government officials who happen to be in the favored Communist Party sub-faction of the moment. Their wealth is then typically expropriated by the state, with the apparent reason ultimately being that the entrepreneur had stepped out of line or was tied to Party officials on the losing end of an internal squabble. The most high-profile recent example was the disappearance of outspoken billionaire Alibaba founder Jack Ma ($40B+ net worth). Ma gave a speech in October 2020 criticizing the Chinese financial system and promoting his own financial services company, Ant Group. He disappeared the following month before resurfacing in January 2021 in a video message that was reminiscent of a hostage situation. He has kept a low profile since, as the Chinese government has gone on to prevent the IPO of Ant Group and to begin its expropriation by the state instead.

This incident seemed to set off a chain of high-profile economic interventions by the CCP in 2021. Chinese officials cracked down on Didi, the “Chinese Uber”, right after its US-based IPO in a manner that appeared calculated to punish it for tapping into US capital markets. Private tutoring businesses in China were banned from being for-profit enterprises around the same time, leading to mass layoffs and the destruction of those companies’ market values. A common thread in the CCP’s rhetoric while carrying out these actions has been the protection of consumer privacy and the reduction of economic inequality. We’re skeptical given the selective enforcement of these principles on companies and business leaders who seem to be threats to the totalitarian rule of the Chinese Communist Party and given the wealth transfers that always seem to follow. These wealth transfers are now starting to surpass the usual scenario of state-owned enterprises (SOE’s) buying large stakes in private companies whose market value has been damaged by state intervention, with many wealthy Chinese now giving away billions to state-linked “charitable” causes in a hurried attempt to appease the government.

Crypto, China & Conclusion

The latest high-profile demonstration of the trend toward more extractive economic institutions in China was last week’s ban on the use of cryptocurrencies in China. The Chinese government issued similar bans in 2013 and 2017 that failed to stop the longer-term trend toward their mining and adoption in the country. While we’re not crypto fanatics, we are sympathetic to decentralized cryptocurrencies that can democratize access to the financial system. One heartening example is the company Strike, which uses a Bitcoin-based payment layer called the Lightning Network to dramatically reduce the cost and risk for workers of sending remittance payments to their families in other countries. We witnessed Strike & the Lightning network being implemented in El Salvador earlier last month as the nation adopted Bitcoin as legal tender (on a separate note, the Lightning Network is also what Twitter is now using for facilitating tipping Twitter profiles with bitcoin). There are many reasons for the overseers of China’s extractive political institutions to want to do away with cryptocurrencies. The principal ones are that they’re a way for Chinese citizens to circumvent government rules to get their wealth out of the country and, more importantly, that the government is working on its own cryptocurrency. Once in the hands of a totalitarian regime like the CCP, digital currencies become tools of extractive economic institutions rather than inclusive ones. A government-controlled digital currency will grant the CCP complete surveillance of citizens’ wealth and transactions, as well as the ability to punish foes by easily confiscating their wealth.

In spite of this worrying trend toward more extractive institutions in China, we remain hopeful for a better future for the country and its citizens. We’re also hopeful that in the case of cryptocurrencies (especially Bitcoin), the USA will seize the opportunity to further democratize its economic system and recreate inclusive economic institutions. We do occasionally worry that the US government will resort to more extractive political institutions to protect the reserve currency status of the US dollar. While the US has enjoyed the fruits of this status since the end of World War II in 1945, it is coming under pressure with the US national debt growing from $9.4 trillion in Q1 2008 (64% of GDP) to $28.5 trillion in Q2 2021 (125% of GDP). Cryptocurrency is just the latest instance where the theories expounded in Why Nations Fail can have utility for policymakers trying to navigate rapid technological progress and other complexities faced in the year 2021.

Let us know your thoughts in the comment section below!

Newsletter Recommendation: The Learn Letter

The Learn Letter is a weekly newsletter exploring evidence-based learning science. It includes actionable advice so you can become an effective learner for life. You can subscribe free here.

We really enjoy Eva’s writing and are already putting some of her tips into practice. If you get a chance to check out her work, let us know what you think!

All the best,

The Citizen Scholar Team

Discussion #8: Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty, by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson